What, that doesn't sound exciting? Would it help if I told you that during the War of 1812, pretty much the only way to obtain imported household items was to do this?:

|

| Thomas Whitcombe, Battle Scene in the English Channel Between the American Ship "Wasp" and the English Brig "Reindeer," 1812. Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago. |

Undoubtedly, similar events were taking place in Maryland during this time, and it is interesting to consider how people might have obtained the everyday items they relied on during a time when trade was completely disrupted - as Miller points out, Napoleon passed the Berlin Decree in 1806, forbidden the importation of British goods; the U.S. passed the Non-Importation Act and the Embargo Act to try to get the British to stop impressing American sailors, but the British kept right on impressing them and terrestrial Americans ended up having a hard time obtaining English manufactured goods.

Evidently, the American passion for English tea services was such that privateers went out and took English dishes (and let's not forget those Irish linens) by force. Next time you see an archaeologist getting all excited about their feather-edged pearlware or mocha dipped mustard pots, and you wonder why everyone is so hot and bothered about ceramics, keep in mind that these poor broken bits of plates and teacups were probably involved in swashbuckling high seas adventures.

Without further ado, I give you:

Ceramics from the 1813 Prize Brig Ann, Auctioned in Salem, Massachussetts: An Analysis

On April 13, 1813, 250 crates of “Liverpool Ware” and 7 cases of “Irish Linens” were auctioned in Salem, Massachusetts. These were the cargo from the prize brig Ann that had been captured by Captain Nathan Lindsey of the privateer schooner Growler. Following the sale of the cargo, the prize ship—described as “The Brigantine ANN, of the burden of 226 tons or thereabouts together with her tackle, apparel and furniture; also three pair of 9 pound Cannonades”—was auctioned as well.

Prize auctions were common in the War of 1812;

what makes this one of great interest is the survival of the auction catalog,

in the Kress Collection of the Baker Library of the Harvard University Business

School.

During the War of 1812,

the United States government issued letters of marque to more than five hundred

privateers who captured about thirteen hundred English commercial vessels. Letters

of marque authorized private, armed vessels to capture vessels of the enemy. In

some cases, the cargo was seized and the prize ship was burned. If the captured

ship was worth taking back to port and the privateer had enough men to spare, it

was declared a prize of war to be sold or auctioned. The proceeds were divided

among the owners of the privateer vessel who financed the venture, the captain,

and the crew, based on the contracted number of shares assigned to each.

The Growler was based in

Salem, Massachusetts. In a discussion of the War of 1812 in his History and Traditions of Marblehead, Samuel Roads Jr. states:

As soon as the news of the declaration of war was received in Marblehead. . . four privateers, namely, the Lion, the Thorn, the Snowbird, and the Industry, were immediately fitted out, and began a series of remarkable successful Cruises against the ships of the British nation. This is not all. Forty private armed schooners were soon fitted out in Salem. . . . One Schooner, the Growler, was commanded by Capt. Nathaniel Lindsey, of Marblehead, and had an entire crew of Marblehead men.

Roads further reports

that the Growler “captured the brig Ann, of ten guns bound from Liverpool to

New Providence, richly laden with dry goods and crates worth $100,000.”

A newspaper from March 6,

1813, announced:

Yesterday arrived at Marblehead, the British brig Ann, (capt. Joseph L. Lee, prize master) from Liverpool bound to N. Providence, with a cargo of dry goods & crates, valued at 80 to 100,000 dollars—She was captured above [sic] 70 days since by the private armed scho. Growler, of this port.

|

| Two pages from the auction catalog, courtesy of Kress Library of Business and Economics, Baker Library, Harvard Business School |

This notice suggests that the brig Ann was captured in late

December 1812.

The auction catalog for the brig Ann lists 250 crates of

ceramics that fall into four basic assortments.

Each type of crate is

enumerated in great detail, followed by the number of crates that contain the

same assortment of vessels. Crate 1, for example, is described as having “40

doz. C. Co. (cream-colored) Plates 1-3d Soups” followed by a note stating that each

of crates 2 through 50 had the same contents as crate 1. The other three assortments

are described similarly but in much more detail, since they include a greater variety

of vessel shapes and decoration types (enumerated in Tables 3–5).

The description of the ceramics follows the format of

invoices used for ceramics shipped from Staffordshire to the American market,

which suggests that the catalog was transcribed from a potter’s invoice.

Unfortunately, the name of the factory or factories that produced the wares and

the designated recipient of the shipment were not recorded. The prices listed for

each lot would also have been taken from the potter’s invoice. Prices for “Dishes”

(a potter’s term for platters) are nearly identical to those in the 1796 and

1814 Staffordshire price-fixing lists, whereas the price of plates is slightly

lower (see Table 1). Unfortunately, the prices realized for each lot are not

recorded in the catalog.

|

| Table 1 |

Descriptions of the Four Crate Assortments

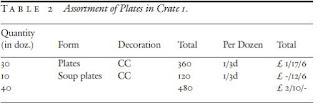

The assortment for crate 1 was listed as “40 doz. C. Co.

Plates 1/3d Soup 1/4 £ 2/13/4 [sic].” These were cream-colored (CC) plates, of

which one quarter were soup plates. The total price of £ 2/13/4 is an error, as

it was calculated by multiplying the 40 dozen by the 1-to-4 mix ratio, rather

than by the 1/3d (1 shilling 3 pence), which was the price. The breakdown is given

in Table 2. Crates 2 through 50 were of the same mix of CC plates as in crate

1, bringing the total to 18,000 plates and 6,000 soup plates—24,000 vessels in

all. The average cost per vessel was 1.25 pence.

|

| Table 2 |

Crate 51 contained an assortment of mostly creamware vessels

(enumerated in Table 3). This would have been known as an “assorted crate,”

meaning it was offered for sale to merchants as a unit only, rather than by the

item. Crates 52–130 are listed as containing the same mix of 455 vessels

enumerated in crate 51. In short, there were 80 crates containing the

assemblage listed for crate 51, for a total of 36,400 vessels. The average cost

of these vessels was 2.7 pence. The auction catalog lists crate 51 as being worth

£5/4/4, but by my calculations in Table 3 it totals £5/3/10, suggesting a math

error in the original tally.

|

| Table 3 |

Crate 131 is another assorted crate, and lists a large

number of blue-edged vessels, which are enumerated in Table 4. This crate

contained 407 vessels and was valued at £5/8/4, for an average value of 3.2

pence. Crates 132 through 180 were listed as containing the same assemblage as that

enumerated in crate 131, so there were 50 crates of blue shell-edged and other

wares, for a total of 20,350 vessels.

|

| Table 4 |

Crate 181 through 250 contained the same assortment of 407

vessels as enumerated for crate 131, but the wares were green shell-edged

rather than blue shell-edged, bringing to 70 the total number of crates with

green edged wares, or 28,490 vessels. A summary of all of the forms, decorative

types, and quantities contained in the crates is presented in Table 5.

|

| Table 5 |

Table 6 illustrates the percentages and ratios of wares by

functional groupings by combining the number of vessels by their decorative

types from all the crates. This is followed by figure 4, a pie chart of the

distribution of the 109,240 vessels grouped by vessel type. The combined

assemblage appears to have had very limited numbers of teawares and no toilet

wares (chamber pots, ewers, basins). However, the

fifty crates of CC plates have distorted the assemblage toward those vessels.

Table 6 illustrates the percentages and ratios of wares by

functional groupings by combining the number of vessels by their decorative

types from all the crates. This is followed by figure 4, a pie chart of the

distribution of the 109,240 vessels grouped by vessel type. The combined

assemblage appears to have had very limited numbers of teawares and no toilet

wares (chamber pots, ewers, basins). However, the

fifty crates of CC plates have distorted the assemblage toward those vessels.  |

| Table 6 |

Table

7 provides a list of the vessel types in the crates that have assorted assemblages.

Teawares still make up a smaller proportion of the assemblages than expected,

and no toilet wares are listed. CC ware (plain creamware) is the dominant type

of the 109,240 vessels from the brig Ann cargo. The second most common type of ware is painted, followed

by green-edged, blue-edged, enameled (overglaze painted), and “fancy” (dipped).

No printed wares are listed in any of the assorted crates.

|

| Table 7 |

The

decorated wares listed, with the exception of the enamel painted, are the

cheapest available with color decoration. There are major differences among the

types of decoration present on tea-, table-, and hollow wares. For example, all

of the teaware is decorated.

All

the cups and saucers are painted. Teapots, sugar boxes, and milk jugs are either

painted or enameled. Tableware (dishes, plates, and serving vessels) are in CC

ware, blue edged, or green edged. Bowls are in CC ware, fancy (dipped),

painted, or enameled decoration. Mugs are in CC ware, fancy (dipped), or

painted decoration. Jugs are CC ware or painted.

Observations on the 250 Crates of

Assorted Ware

Table

8 is a summary of the total cost of the ceramics in the 1813 auction catalog.

The summary of the value of the crates of earthenware in the 1813 auction

catalog was listed as £1,300/13/4, which is close to the calculations in Table

8. Dividing the $5,567.77 by the 109,240 vessels yields an average value of

five cents per vessel. The value of the pound sterling for these calculations was

taken from value of the dollar from the exchange rates of 1816.

|

| Table 8 |

The

total value of the ceramics is far short of the estimated value of the prize,

which in the newspaper announcement of March 6, 1813, was between $80,000 and

$100,000. The value of the textiles came to £5,543/9/8.5, which in the 1816

exchange rate of the dollar was $25,333.73. Thus the value of the ceramics was

only 18 percent of the cargo and the textiles was 82 percent of the cargo.

Together they came to $30,901.50, which was well below the estimated value of

the prize. Clearly, the estimate of the value of the prize included the value

of the brig Ann. Unfortunately, we do not know the prices realized; a follow-up

newspaper article on the auction is not known. One would assume that the

English ceramics and textiles brought a premium price during the War of 1812,

when the supply of them was limited to prizes taken for auction. In addition,

the currency was inflated by the War of 1812, which makes the question of

prices difficult to answer. All of the assorted crates of CC, blue-edged, and

green-edged wares included other types of decorated vessels. Assorted crates

have a long history in the pottery industry. By the late eighteenth century,

merchants specializing in ceramics and glass took special orders made up of the

vessels wanted by retail merchants.9 Assorted crates represent what the potter

or wholesaler thought would be a marketable assemblage to retailers. The assorted

crates described above are unusual in the relatively small percentage of

teawares included. For example, the CC crates did not include any cups and

saucers.

The

Market for English Ceramics in 1813

Napoleon’s

1806 Berlin Decree cut off the European Continental market for British products,

and this, followed by the American Embargo of 1807,the

Non-Importation Act, and the War of 1812, eliminated the important American

market for English manufactured goods. The many American privateers preying on

English ships aggravated the economic situation. The South American market was

opening because of the revolutions for independence that took place while

French and English armies occupied Spain. The Caribbean market was open, but

dangerous because of the privateers.

The

brig Ann is listed as having sailed out of

Liverpool for New Providence, the main island of Bermuda. It was probably

headed for St. George, the main port town on the island. Following the American

Revolution, it is estimated that eight thousand loyalists from the American

South, including plantation owners and their slaves, immigrated to Bermuda. The

population of the islands tripled, three-quarters being slaves. During the Napoleonic Wars the British built a complex of

military forts and a naval dockyard. Military operations provided a cash inflow to Bermuda and

provided employment for many on the islands. Many prize ships captured by British

privateers out of Bermuda and by the British Navy wound up being auctioned off in Bermuda during the Napoleonic Wars

and the War of 1812. These

activities and Bermuda’s history as a center for illicit trade help to explain

why the prize brig Ann would

be headed there when the European continent and the American markets were

closed off to

the British.

The

presentation of the auction record of the brig Ann’s cargo offers a rare glimpse into the tremendous quantities of the

standard tablewares produced by the English potters and imported into this

country during its formative years.

*The End*

As always, if you want to see some of the historic ceramics described here or found more generally at sites in Maryland, I refer you to the excellent "Diagnostic Artifacts in Maryland" pages over at Jefferson-Patterson Park & Museum.

Posted 1/23/2013 by Lisa Kraus